When COVID-19 ruins your plans!

The group of Year 8 students had just finished a unit of work on the history of the Catholic Church from the fall of Rome to the Reformation as part of their Religious Education subject (Curriculum link – ACDSEH052/ ACDSEH054). At the culmination of the semester, they were supposed to go on an excursion to explore the various different Christian churches and analyse how their structure, design, and use of symbols support faith based practices (Curriculum link – ACAVAM119/ACHASSK198).

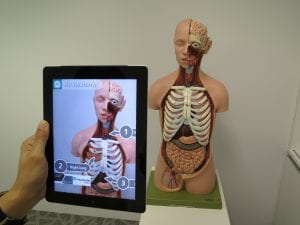

However, the COVID-10 pandemic and resulting restrictions prevented that adventure. Therefore, in an effort to address the gap in their learning, the teacher librarian and classroom teacher collaborated to create a lesson that would virtually explore various churches by introducing emerging technologies in the form of virtual reality to the classroom with Google Cardboard and Google Streetview. In the process students would learn essential note taking skills using a graphic organiser and paragraph writing skills. Evidence of learning would be the written TEXAS or TEEL paragraph illustrating their analysis of the building structure and design and how it supports faith practices and community.

Rosenblatt’s reader response theory was the underlying pedagogical principle for this activity (Woodruff & Griffin, 2017, p.110). Commonly used in literature circles, Rosenblatt’s constructivist theory acknowledges each student’s contribution as valid, which enables them to become active agents in their own learning, and the activity appropriate for a diverse classroom (Woodruff & Griffin, 2017, p.109-110). However, instead of investigating texts in a literature circle, the students investigated and analysed religious sites in a similar immersive experience. This virtual exploration required them to combine the new visual information to their own prior experience in order to create new knowledge (Woodruff & Griffin, 2017, p.111). The collaborative atmosphere allows students to have an equal exchange of ideas, increases their problem solving skills as well as developing interpersonal skills and promotes collegian discussion (ACARA, 2014a; Tobin, 2012, p. 41).

The students were given a choice of six different churches to visit and had to select three for comparison purposes. As location was no longer an issue, the TL identified a variety of churches from different Christian denominations across the world that were suitable. It is important that careful research be undertaken to ensure that the sites are accessible freely via Google Streetview and the associated images provide relevant information.

The students were requested to note down the similarities and differences between the different types of churches using a triple venn diagram. This part of the task involved student collaboration and ideally students would have selected a different church site each and then shared their information through discourse. However this did not happen as the students all looked at sites sequentially rather concurrently, which was a poor use of time from a teacher perspective, but did increase the length and breadth of discourse.

Teaching note taking and the use of graphic organisers simultaneously was a pedagogical strategy. Note taking is an essential skill that needs to be explicitly taught across the curriculum as the style of note taking and vocabulary choice will vary depending on the discipline. Good note takers have generally higher academic outcomes because they are able to succinctly summarise ideas, concepts and information using their own vernacular, and then use their notes to create content to communicate their understanding and analysis (Stacy & Cain, 2015). Graphic organisers have been proven to improve learning outcomes because it increases connections between ideas, and organises information in a visual and spatial manner (McKnight, n.d.; Mann, 2014). By utilising the two strategies together, the students are given an opportunity to explore different methods of learning which they can use throughout their learning both in and outside classroom walls.

Good notes lead to a strong author’s voice and content in paragraphs. The culmination of the task required students to create a paragraph identifying and describing the structure of the church and its alignment to faith based practices, as well as evaluating how the design of the church’s spiritual and aesthetic design holds value to their congregation and society. The question was created using Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive domains so that all the diverse learning needs of the class would be catered for appropriately (Kelly, 2019b).

Questions are an intrinsic and ancient practice of teaching (Tofade, Elsner & Haines, 2013). Carefully designed questions are all features of good pedagogical practice and are able to, stimulate thinking, promote discourse, further connections between prior and new knowledge as well as encourage subject exploration. (Tofade et al., 2013). Teachers that stage questions in order of Bloom’s taxonomy are addressing all the cognitive domains, as well as building students to achieve that higher order thinking (Tofade et al., 2013).

The virtual exploration of churches around the world was designed to compensate students for their inability to connect their learning to the real world to the pandemic. The task overtly sought to get students to experiment with emerging technologies, work in collaborative groups and communicate their learning in written form. In addition students covertly learned to note take using graphic organisers, engage in collegial discourse and use Bloom’s taxonomy to work toward higher order thinking. These skills are in addition to the content learning outcomes and even if the students did not learn any new content, they had a good crack at learning some valuable skills!

Curriculum links:

Overall content outcomes:

- ACDSEH052 – Dominance of the Catholic Church and the role of significant individuals such as Charlemagne

- ACDSEH054 – Relationships with subject peoples, including the policy of religious tolerance

- ACAVAM119 – Analyse how artists use visual conventions in artworks

- ACTDIP026 – Analyse and visualise data using a range of software to create information, and use structured data to model objects or events

- ACHASSK198 – Identify the different ways that cultural and religious groups express their beliefs, identity and experiences

- ACELA1763 – writing structured paragraphs for use in a range of academic settings such as paragraph responses, reports and presentations.

- ACELY1810 – Experimenting with text structures and language features to refine and clarify ideas and improve text effectiveness.

(ACARA, 2014h; ACARA, 2014i; ACARA, 2014j)

Using VR

- GC – ICT -Locate, generate and access data and information

- GC – CCT – Identify and clarify information and ideas

- GC – Literacy – Understanding how visual elements create meaning (ACARA, 2014c; ACARA, 2014b; ACARA, 2014h)

Graphic organisers

- GC – CCT –

- Organise and process information

- Imagine possibilities and connect ideas (ACARA, 2014b)

Collaborative Learning groups

- GC – PSC

- Appreciate diverse perspectives

- Understand relationships

- Communicate effectively

- Work collaboratively

- Negotiate and resolve conflict

(ACARA, 2014d)

TEXAS Paragraph

GC – IC –

- Investigate culture and cultural identity

- Explore and compare cultural knowledge, beliefs and practices

GC – Literacy

- Compose spoken, written, visual and multimodal learning area texts

- Use language to interact with others

- Use knowledge of text structures

- Express opinion and point of view

- Understand learning area vocabulary

(ACARA, 2014f; ACARA, 2014c)

REFERENCES

ACARA. (2014a). Personal and social capability. General Capabilities Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/personal-and-social-capability/

ACARA. (2014b). Creative and critical thinking continuum. F-10 Curriculum – General Capabilities Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/1072/general-capabilities-creative-and-critical-thinking-learning-continuum.pdf

ACARA. (2014c). Literacy continuum. F-10 Curriculum – General Capabilities Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/3596/general-capabilities-literacy-learning-continuum.pdf

ACARA. (2014d). Personal and social capabilities continuum. F-10 Curriculum – General Capabilities Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/1078/general-capabilities-personal-and-social-capability-learning-continuum.pdf

ACARA. (2014e). Ethical understanding continuum. F-10 Curriculum – General Capabilities Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/1073/general-capabilities-ethical-understanding-learning-continuum.pdf

ACARA. (2014f). Intercultural understanding continuum. F-10 Curriculum – General Capabilities Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/1075/general-capabilities-intercultural-understanding-learning-continuum.pdf

ACARA. (2014h). Information and communication technology capability learning continuum. F-10 – General Capabilities Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/1074/general-capabilities-information-and-communication-ict-capability-learning-continuum.pdf

ACARA. (2014h). English. F-10 – General Capabilities Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/english/?strand=Language&strand=Literature&strand=Literacy&capability=ignore&priority=ignore&year=11582&elaborations=true&el=15718&searchTerm=TEEL+paragraph#dimension-content

ACARA. (2014i). History Curriculum. F-10 Curriculum – Humanities and Social Sciences Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. . Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/humanities-and-social-sciences/history/

ACARA. (2014j). Visual Arts Curriculum. F-10 Curriculum – Humanities and Social Sciences Curriculum. Educational Services Australia. . Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/the-arts/visual-arts/

Kelly, M. (2019a). Organising compare-contrast paragraphs. ThoughtCo [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/organizing-compare-contrast-paragraphs-6877

Kelly, M. (2019b). Bloom’s taxonomy in the classroom. ThoughtCo [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/blooms-taxonomy-in-the-classroom-8450

Mann, M (2014). The effectiveness of graphic organisers on the comprehension of social studies content by students with disabilities. Marshall University Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Retrieved from https://mds.marshall.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1895&context=etd

McKnight, M. (n.d.). Use graphic organisers for effective learning. TeachHUB.com. Retrieved from https://www.teachhub.com/teaching-graphic-organizers

Stacy, E., & Cain, J. (2015). Note taking and handouts in the digital age. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education (79) 7. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4812780/

Tobin, M. (2012). Digital storytelling: Reinventing literature circles. Fischer College of Education. 12. NSU. Retrieved from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=fse_facarticles

Tofade, T., Elsner, J., Haines, S. (2013). Best practice strategies for effective use of questions as a teacher tool. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 77 (7). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3776909/.

Woodruff, A., & Griffin, R. (2017). Reader response in secondary settings: Increasing comprehension through meaningful interactions with literary texts. Texas Journal of Literacy Education (5) 2 pp.108-116. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1162670.pdf