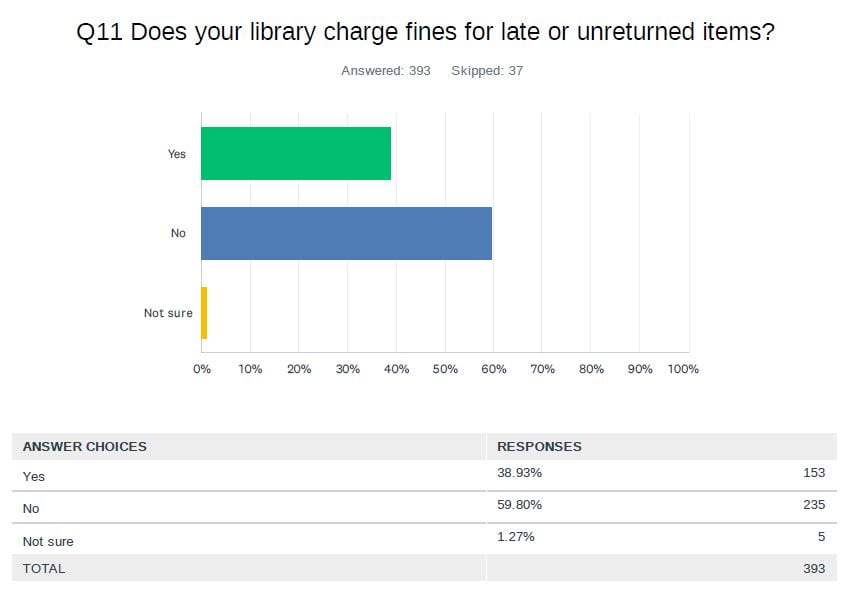

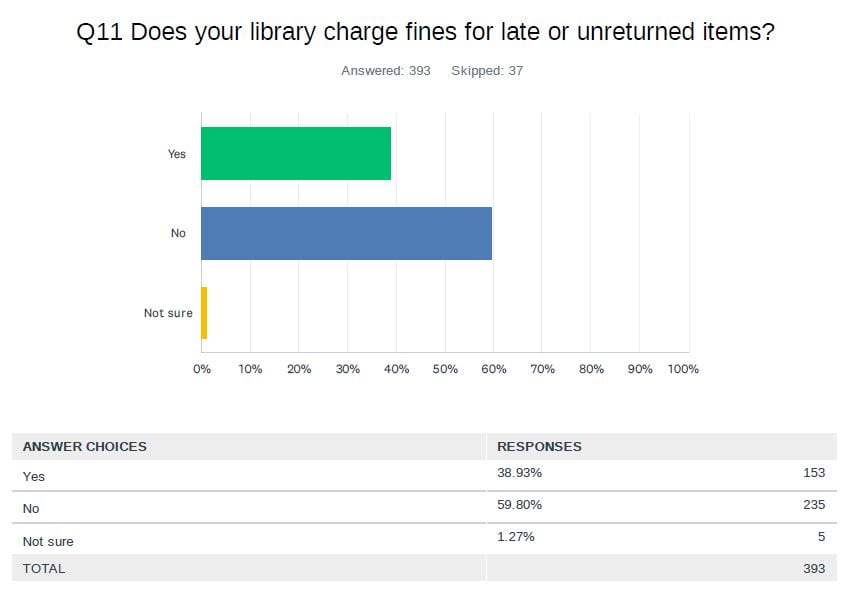

In a national survey of Australian public library workers I asked the question: “Does your library charge fines for late or unreturned items?” This is a significant question because it is possible and perhaps likely that people experiencing homelessness and/or poverty could be avoiding using public libraries in case they get charged fines they can’t afford to pay back.

I thought this practice had largely disappeared as a way to remove a barrier libraries have placed between people and library resources in the past. It turns out that this is not the case in many of our libraries at the moment. Here are the results to the question:

What this is telling us is that of the 393 people who answered this question, 235 of them work in libraries that do not fine people for late or unreturned books, while 153 people work in libraries that do charge fines. Five people weren’t sure what their library did about this.

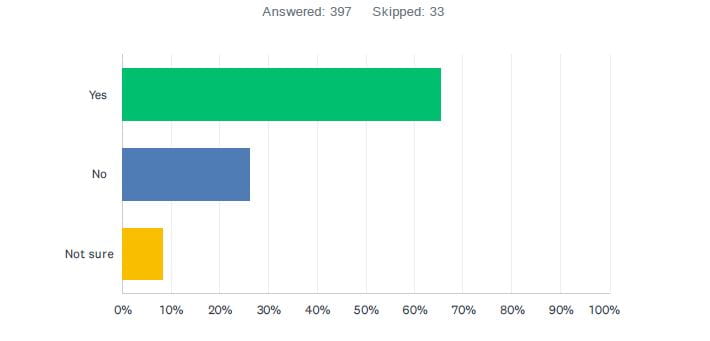

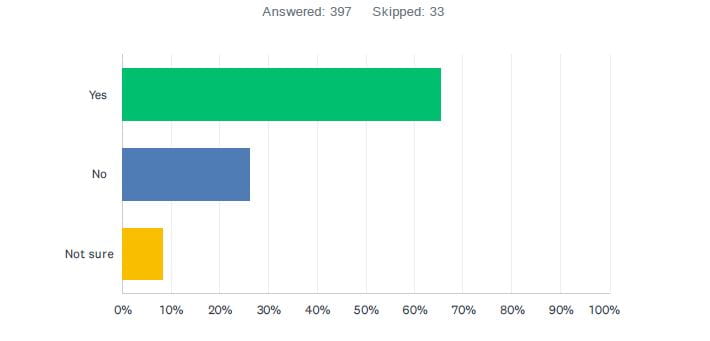

This made me wonder where are these libraries are that are still charging fines? This is what the data is telling us about where the libraries that are still charging fines are located:

So, the green colour indicates States/Territories where more people have said there are no fines charged in their library than those who do charge. The red indicates States/Territories where more people have said their library charges fines than those who don’t. The Australian Capital Territory, the Northern Territory and South Australia have more respondents saying their libraries charge fines than those who say their libraries don’t. But more respondents in Queensland, Tasmania and Victoria say their library doesn’t charge fines than those who say their libraries do charge fines. New South Wales and Western Australia were about half and half. This could mean that people experiencing homelessness and/or poverty are less likely to use their public library in the ACT, NT and SA than in the other states to avoid getting library fines.

What do you think? Should all libraries remove their fines for late or unreturned books as a way of reducing barriers to library use? Or are there good reasons for maintaining the practice of fining our library users? Are you surprised that so many of us work in libraries that are still charging fines?

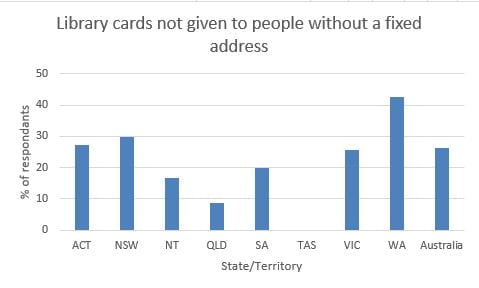

In a national survey of Australian public library workers, 397 people answered the question “Does your library issue library cards to people with no fixed address?” This is how the responses look:

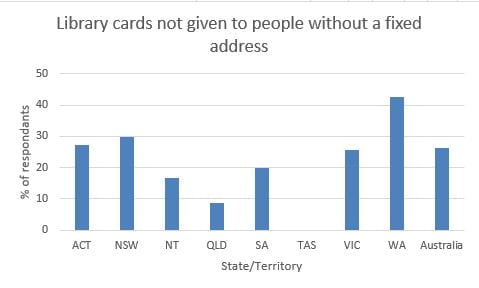

26.2% (104 respondents) say they work in a public library that still requires people to have a stable home address before they are allowed to take full advantage of what those libraries can offer. This got me thinking about where these respondents were. What State or Territory has the highest percentge of their total responses indicating their libraries require a stable home address before people can use libraries in the same way that people with homes can? This next chart answers that question:

It turns out that Western Australia had a higher percentage of their respondents indicating their libraries needed a person to have a fixed address before they were allowed to have a library card than any other state or territory. New South Wales was the next highest response, and no respondent in Tasmania stated that library cards are only issued to people with a fixed address.

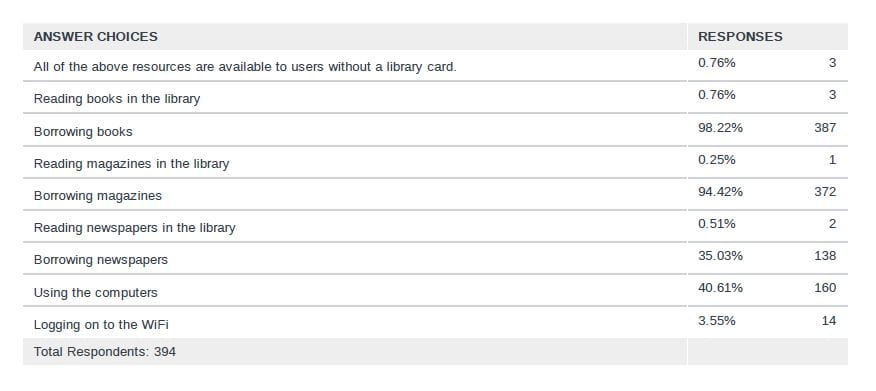

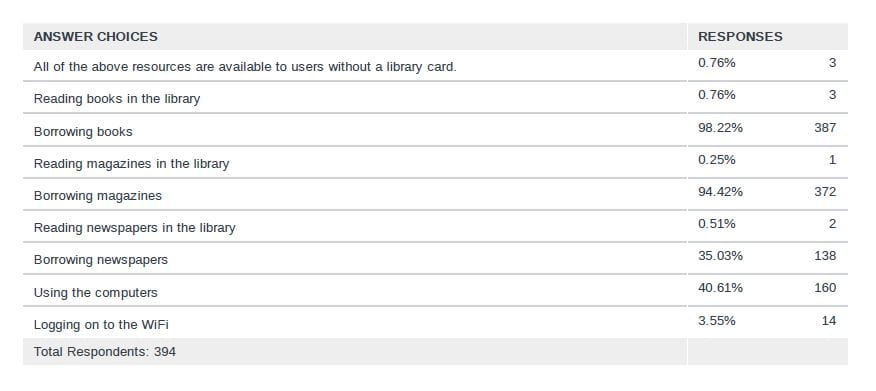

Then I started to think about what people without library cards are missing out on because they have no fixed address. In the survey I asked respondents to indicate which of their services were only available to people with library cards. This is what the response looked like:

What this is telling me is that people who are not allowed a library card due to their lack of a fixed address are very likely to be missing out on borrowing books, magazines and newspapers. They are often unable to use a computer, and in some cases can not log on to the library WIFI. Three respondents said they offer no services at all to people without library cards.

What do you think? Is it right to deny our adults and children without a fixed address access to a public library service?

A question asked of Australian library staff in a project survey was: ‘How often are you aware of people in your library whom you or other staff think may be experiencing homelessness?”. These are the results of this question from 413 responses:

- Never: 4 responses

- A few times a year: 82 responses

- A few times a month: 71 responses

- Once or twice a week: 77 responses

- Daily: 179 responses

This is how those numbers look across each of our states and territories (these numbers look a little different to the above because some people answered this question, but did not answer the question about what state or territory they were from. These people are not represented in this table.):

| Location |

ACT |

NSW |

NT |

QLD |

SA |

TAS |

VIC |

WA |

Total |

| Never |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

2 |

| A few times per year |

2 |

26 |

|

8 |

10 |

3 |

11 |

14 |

74 |

| A few times per month |

3 |

22 |

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

13 |

16 |

63 |

| Once or twice per week |

1 |

24 |

|

7 |

6 |

3 |

13 |

16 |

70 |

| Daily |

5 |

32 |

6 |

17 |

26 |

7 |

45 |

20 |

158 |

So what can we learn from these results? What this is telling us is that every state or territory except Western Australia has library staff that see people they think might be experiencing homelessness in their libraries at least a few times a year. Library staff who are seeing people they think might be without homes in their libraries are most likely to be seeing this every day.

It is worth noting that these responses were based on library staff observing people who appeared to be homeless. Participants were not asked what they saw in a person that made them believe that person was homeless, but it is possible that the people they observed were sleeping rough, and that their appearance reflected this. When we consider that only 7% of people experiencing homelessness are sleeping rough (Mission Australia, 2021), there is a very good chance that there are many more people than this table indicates who are without homes and are using our libraries.

More reporting from the survey will follow soon.