Part A: Personal philosophy

An effective teacher librarian (TL) has comprehensive knowledge of students, curriculum, literature and library and information management. They have intimate knowledge of their local school community and have the school’s mission at the heart of all they do. Effective TLs use outstanding communication skills to collaborate with teaching staff to implement teaching and learning programs that promote information literacy, reading for pleasure and lifelong learning. They provide a safe, welcoming and well-resourced space for students and staff. An effective TL is an expert in collection development and management. They are constantly evaluating their practice and will strategically plan and budget for continued improvement.

Part B

Three of the biggest takeaways from this Masters of Education (Teacher Librarianship) for me have been around collection development and management, information literacy and leadership. While a love of literature is what drew me to the library (Doherty, 2019, March 11), I now know that the scope of the TL role is much broader than this alone.

Collection Development

In one of my earliest blog posts (Doherty, 2019, March 11) I refer to my initial impressions of the TL role as being like children’s services of a public library on steroids. Of course I could see that to facilitate this the TL “would have to purchase, organise and care for the collection” but “I grossly underestimated the amount of time this took” (Doherty, 2019, Mar 11). Working in the role of TL while concurrently studying this course has allowed me to apply my learning in real time. I was very fortunate to take over the TL role from a colleague who went out of her way to facilitate a smooth transition. She gave me training in the Oliver library system in terms of accessioning new resources and getting them shelf ready. However, as I stated in an early blog post (Doherty, 2019, May 20) there was no policy or procedures manual in sight. Through ETL503: Resourcing the Curriculum I have been made aware of the necessity for these documents and how to go about writing them. I have found Debowski (2001), Johnson (2018), Australian Library and Information Association Schools and Victorian Catholic Teacher Librarians [ALIA & VCTL] (2017) and the National Library of New Zealand [NatLibNZ] (n.d.a) invaluable resources in developing our school library policy and procedures documents. These documents underpin and validate the collection update currently underway (Doherty, 2019, May 26a). The first stage of our update has been to identify and weed dated and worn/damaged resources that were contributing to a substantial physical collection but becoming a distraction rather than an asset (Dillion, 2001) and hiding the quality resources that were there (Doherty, 2019, May 26a). Next, a thorough collection analysis is planned, using Oliver analytical reports to inform as well as surveys of staff, students and community on what they expect/want from our library (NatLibNZ, n.d.b; (Doherty, 2019, May 26a).

ETL503: Resourcing the Curriculum also introduced me to the idea of a ‘balanced’ collection in numerous ways. I now know consideration must be given to the following as I undertake the collection analysis and in all collection development and management decisions going forward:

- Content vs Container

- Ownership vs Access

- Single Title vs Bundle Sets

- Physical vs Digital

- Fiction vs Nonfiction

- Quality vs Popular.

When I took over, our library’s digital collection was non-existent (Doherty, 2019, May 20; 2019, May 26a). My knowledge in this area is lacking (Doherty, 2020, July 26) but is continually growing thanks to this course and subjects like ETL503: Resourcing the Curriculum, ETL402: Literature Across the Curriculum and INF533: Literature in Digital Environments. In working towards a balanced collection, a goal to develop our digital collection has been included in the library policy and e-book, online encyclopaedia and Clickview subscriptions have been purchased.

The New South Wales Department of Education’s (NSW DET) library policy (2020) outlines the role of the school library in supporting teaching and learning in the context of syllabus and curriculum requirements and providing resources to teach the curriculum. All collection development and management decisions must keep this in mind. The necessity for a balanced collection is again highlighted when considering this. The NSW English syllabus requires students to study spoken, print, visual, media, multimedia and digital texts (NSW Education Standards Authority [NESA], 2012, p.22), for example. However, as we learnt in ETL402: Literature Across the Curriculum, the benefits of literary learning across the curriculum cannot be underestimated. Whereas literacy learning is learning about literature, decoding, literary devices and such usually reserved for the English curriculum area, the act of literary learning is learning across any and all curriculum areas through quality literature. Ancient cultures have been telling stories, sometimes accompanied by carvings or rock paintings for millions of years. Story, or narrative, remains one of the most powerful ways we can find out about the world and the primary way humans organise our experiences of the world (Lehman, 2007; Murdoch, 2019). The experience of creating resource lists for key learning areas and cross curriculum priorities in this subject as well as ETL503: Resourcing the Curriculum has been enjoyable and incredibly practical for immediate use in the school library. It is a practice I plan to continue in my role as TL.

From thinking the TL role mostly involved circulation and occasionally purchasing new books (Doherty, 2019, May 26a), my knowledge in the area of collection development and management has grown immensely and an appreciation of its intricacies, the time that must be dedicated to it and the implications for teaching and learning across the school established.

Information Literacy

As indicated above, I had not given much thought to the library as much more than a literature hub before moving into the role and beginning this course. In an early blog post (Doherty, 2019, Mar 11) I said I had an inclination that the digital age and the 21st century learner would have an impact on library operations, as it did school wide, but it was quickly becoming apparent just how big of an impact! In the same blog post I refer to my frustration as a classroom teacher with the quality of research my students would provide and Hutchinson (2017) let me know I was not alone. It was also Hutchinson (2017) who made it very clear to me that it is now more important than ever in our ‘google everything’ society that students are armed with the skills to search a database, use keywords and research techniques, evaluate where their information comes from and be aware of plagiarism, copyright and the consequences of poor research (Doherty, 2019, Mar 11; May 26b). Such is the importance of information literacy to the TL role, the NSW DET library policy (2020) makes specific mention of it; ‘Teacher-librarians provide students with opportunities to develop information skills and to use these skills competently and with confidence for lifelong learning.’

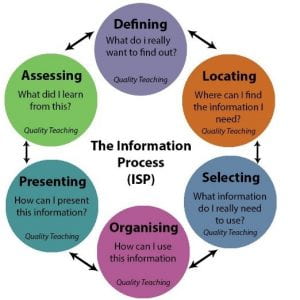

So, there is no question that students need to develop information literacy and that the library and TL must act as catalysts for this. But how? Before completing ETL401: Introduction to Teacher Librarianship I was unsure (Doherty, 2019, Mar 11; May 26b). Thankfully this subject introduced me to various inquiry learning models. As a classroom teacher I was unaware of them and had only stumbled upon the NSW Information Search Process (ISP) since beginning in the library (Doherty, 2019, May 26b). I had introduced this to some stage two and three students and had some success with it guiding them in their research.

However, the model that stood out to me the most in this subject was the Guided Inquiry Design (GID) process as it ‘places great importance on initially building students’ background knowledge before launching students into the research tasks’ (Scheffers, 2008). Given the low socio economic status of much of our student population, background knowledge is often lacking. Thus the dedicated phases of Open, Immerse and Explore in the GID process make it an attractive information literacy model. The remaining phases of the GID process are very similar to the DET ISP and Dawson & Kallenberger (2015) state, ‘A guided inquiry approach, and reference to other information process models, may further enrich the development of information literacy skills’ (p. 3). Thus the GID process could very easily be implemented in NSW DET schools. The wealth of resources available and research demonstrating positive results from its implementation (FitzGerald, 2011) further support use of the GID process. FitzGerald (2011) also advocates for the GID process as a vehicle for evidence based practise in the library which aligns well with our school mission.

While the theory of the GID process is sound, putting it into practice in a collaborative way can prove challenging. Allowing enough time for each phase, while also encouraging students to borrow and try to grow the reading culture of the school is difficult and collaboration with classroom teachers can seem romantic when days can pass without seeing another adult (Doherty, 2019, May 26b). In my blog post, May 26 2019, I indicated that these obstacles were worth figuring out but I anticipated time and some trial and error would be needed. Over the past 12 months, trial and error is what I have been implementing! While I have been trying to use the GID process in my planning and teaching and learning programs, little collaboration with classroom teachers has occurred. Yes, COVID-19 has contributed to that but even so, I feel that I needed to get my head around it a bit more before bringing classroom teachers into the mix. I have begun to share with them some of the lessons we have done in the library using the GID process, and the evidence of student learning in information literacy. The plan is for next year to start on the front foot, with classroom teachers much more aware of the role the library and TL has to play in promoting information literacy so that they and I can work together to see where it would best align within their teaching/learning programs and how we can work together to achieve the best results for students.

Leadership

The TL can also act as servant leader to lead the development of the collection and empower staff and students to gain maximum benefit from it, as touched on in collection development and management above. I work collaboratively with staff and students to determine digital collection needs before sourcing and including them in the collection. Email requests are encouraged and surveys of staff and students conducted to gauge interest/needs. The servant leader’s role does not end here however. The TL must promote, educate, model and inspire staff and students, based on their individual needs, to get the most out of the library’s collection. I have found this easiest to do for students, who visit the physical library space weekly. Staff rarely visit the space however, so I am working on initiatives for teachers such as a greater presence online, in the staffroom and via regular meetings.

In my blog post May 4, 2019 I highlighted how limited my knowledge of copyright law and its impact on teachers was. I acknowledged the importance of following this up as I have no doubt that other teachers and even leadership at our school feel the same. The smartcopying website, creative commons and Roadshow cocurricular licence were all new to me and through ETL503: Resourcing the Curriculum I can now see it is my responsibility as TL to become the expert at our school on matters such as these and actively promote adherence to copyright laws by staff and students. This is something I have begun to do, using the smartcopying website to justify a change in procedure with executive (Doherty, 2019, May 26a) and introducing students to the concept of copyright, creative commons and how to cite sources they are using. I must continue to actively lead and support these changes to embed such practices as standard across the school.

From my very limited knowledge of what the TL role really entailed prior to this Masters, my head is now swimming with ideas and I am excited for the opportunity I have been given to lead our school in developing a balanced collection to meet the needs of our community, moving towards collaborative information literacy teaching/learning and copyright compliance, as well as promoting a reading culture as I first set out to do. As Boanno (2011, 2015) taught me ‘It is up to us to make the profession not just visible but stand out!’ (Doherty, 2019, Apr 24).

Bonanno, K. (2011). Keynote speaker: A profession at the tipping point: Time to change the game plan. Australian School Library Association. Vimeo.

Part C

Completing the Master of Education (Teacher Librarianship) has assisted me immensely in developing the skills and attitudes of a professional teacher librarian. For starters, it has introduced me to documents such as the Australian School Library Association/Australian Library and Information Association [ASLA/ALIA] Standards of professional excellence for teacher librarians, which provide succinct expectations for those in the role that I aim to address below.

1 Professional knowledge

My Master of Teaching (Primary) and twelve years of classroom teaching equipped me with many of the skills and attitudes required of standards 1.2 and 1.3. The exception would be reference to information literacy in 1.2, of which I had very limited knowledge prior to this Masters as indicated in Part B. Similarly, my ability to meet standard 1.1 has been greatly enhanced by this Masters. Information literacy theory and practice has been a strong theme throughout the course which has equipped me with knowledge and skills to evaluate and use various information search process models. With the GID process proving most appropriate in our school setting as outlined in Part B.

Standard 1.4 was completely new to me and without this Masters would still be extremely limited. ETL505: Describing and Analysing Education Resources introduced me to the Schools Information and Cataloguing Service (SCIS) standards for cataloguing, Resource Description and Access Toolkit as well as Web Dewey. This subject provided a steep but necessary learning curve. SCIS is used for all cataloguing in our school library and staying in contact with them and up to date with their procedures and services will be an ongoing process if I am to be an excellent TL.

Farkas, L. & Rowe, H. [CSU Media Services]. (2018, May 7). Introducing WebDewey. YouTube.

2 Professional practice

My very first assignment in this course was looking at the library as a learning environment which has already proved very useful as I led an update of our library space, purchasing new shelving and furniture to allow more flexible and agile use of the space, and assisting me in working towards meeting standard 2.1.

As indicated in Part B, the need for collaborative practice is something that has been highlighted in this course and something I need to continue to strive for if I am to meet standard 2.2 and be an excellent TL. This will be a main goal of mine for 2021. Taking on a servant leadership role will be required as the skills and needs for each teacher to participate in collaborative practice will vary.

Standard 2.3 would not have been within my grasp without this Masters. Our library did not have any written policies or procedures, strategic plans or evidence of alignment with national standards. ETL503: Resourcing the Curriculum and ETL504: Teacher Librarian as Leader provided me with the skills necessary to create such documents. As with everything we do, constant revision of these is required and doing so will assist me to also meet standard 2.4.

3 Professional commitment

As outlined in Part B, leadership was not something I saw in the TL role prior to this Masters. It is something I have slowly been working towards and will set as a goal in 2021, to more actively strive to meet the requirements of an excellent TL in regards to standard 3.3. Engaging in professional networks as per standard 3.4 will certainly support me in doing so. I am a member of our local TL network and attend their annual conference as well as attend the DET TL online update meetings each term, both I plan to continue doing for as long as I am in the role. I must model lifelong learning, standard 3.1, by not seeing the completion of this Masters as the end of my learning journey, rather it is just the beginning!

References

Australian Library and Information Association Schools & Victorian Catholic Teacher Librarians (2017). A manual for developing policies and procedures in Australian school library resource centres (2nd ed.). https://www.alia.org.au/sites/default/files/ALIA%20Schools%20policies%20and%20procedures%20manual_FINAL.pdf

Australian School Library Association & Australian Library and Information Association. (2004). Standards of Professional excellence for teacher librarians. https://www.alia.org.au/about-alia/policies-standards-and-guidelines/standards-professional-excellence-teacher-librarians

Bonanno, K. (2011). Keynote speaker: A profession at the tipping point: Time to change the game plan. Australian School Library Association. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/31003940

Bonanno, K. (2015). A profession at the tipping point (revisited). ACCESS, 14 – 21. http://kb.com.au/content/uploads/2015/03/profession-at-tipping-point2.pdf

Burkus, D. (2010, April 1). Servant leadership theory. In DB: David Burkus. http://davidburkus.com/2010/04/servant-leadership-theory/

Dawson, M. & Kallenberger, N. (Eds.) (2015). Information skills in the school: engaging in construction knowledge. NSW Department of Education. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/curriculum/learning-across-the-curriculum/school-libraries/media/documents/infoskills.pdf

Debowski, S. (2001). Collection management policies. In K. Dillon, J. Henri & J. McGregor (Eds.), Providing more with less: collection management for school libraries (2nd ed., pp. 126-136). Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University.

Dillon, K. (2001). Maintaining collection viability. In K. Dillon, J. Henri & J. McGregor (Eds.), Providing more with less: collection management for school libraries (2nd ed., pp. 241-254). Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University.

Doherty, H. [hayley.walker9] (2019, March 11). Assessment 1 Part B. Learning to Library. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/learningtolibrary/2019/03/11/assessment-1-part-b/

Doherty, H. [hayley.walker9] (2019, May 20). Creating a collection development policy. Learning to Library. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/learningtolibrary/2019/05/20/creating-a-collection-development-policy/

Doherty, H. [hayley.walker9] (2019, May 26a). Assessment item 2, Part B: Reflective Practice. Learning to Library. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/learningtolibrary/2019/05/26/assessment-item-2-part-b-reflective-practice/

Doherty, H. [hayley.walker9] (2019, May 26b). Assessment Item 3, Part C: Reflective Practice. Learning to Library. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/learningtolibrary/2019/05/26/assessment-item-3-part-c-reflective-practice/

Doherty, H. [hayley.walker9] (2019, October 8). ETL504 Assessment item 2: Part B. Learning to Library. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/learningtolibrary/2019/10/08/etl504-assessment-item-2-part-b/

Doherty, H. [hayley.walker9] (2019, April 24). Are school librarians an endangered species? Learning to Library. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/learningtolibrary/2019/04/24/are-school-librarians-an-endangered-species/

Doherty, H. [hayley.walker9] (2020, July 26). Literature in digital environments: Assessment item 1. Learning to Library. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/learningtolibrary/2020/07/26/literature-in-digital-environments-assessment-item-1/

Farkas, L. & Rowe, H. [CSU Media Services]. (2018, May 7). Introducing WebDewey. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ieA5_T1LZy4&feature=youtu.be

FitzGerald, L. (2011). The twin purposes of guided inquiry : guiding student inquiry and evidence based practice. Scan 30(1), 26-41.

Green, G. (2011). Learning leadership through the school library. Access, 25(4), 22-26. Retrieved from http://www.asla.org.au/publications/access.aspx

Guided Inquiry in Australia. (2020, June 17). Teachers and teacher librarians doing GI. https://guidedinquiryoz.edublogs.org/teachers-doing-gi/

Guided Inquiry in Australia. (2015, December 15). GI Theory. https://guidedinquiryoz.edublogs.org/theory-2/

Hutchinson, E. (2017). Navigating the Information Landscape through Collaboration. Connections Issue 101. http://www2.curriculum.edu.au/scis/issue_101/articles/navigating_the_information_landscape.html

Johnson, P. (2018). Fundamentals of collection development and management (4th ed.) ALA Editions. Retrieved from Proquest Ebook Central.

Lehman, B. A. (2007). Skills instruction and children’s literature. Children’s literature and learning: literacy study across the curriculum (pp. 43-56). Teachers College Press.

Maniotes, L. K., & Kuhlthau, C. C. (2014). Making the shift. Knowledge Quest, 43(2), 8-17. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1045936.pdf

Murdoch, K. (2015, October 26). Inspiring inquiry through picture books. Kath Murdoch: Education Consultant. https://www.kathmurdoch.com.au/blog/2015/10/26/bo3tpx8qkbkn6vwtemuj674amslke8

National Library of NZ. (n.d.a). Collections and collection management. National Library of New Zealand Services to Schools. https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/school-libraries/collections-and-resources/collections-and-collection-management.

National Library of NZ. (n.d. b).Working out your library’s collection requirements. National Library of New Zealand Services to Schools. https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/school-libraries/collections-and-resources/collections-and-collection-management

Nichols, J. D. (2010). Teachers as servant leaders. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

NSW Department of Education (2020, February 12). Library Policy- Schools. https://policies.education.nsw.gov.au/policy-library/policies/library-policy-schools

NSW Education Standards Authority. (2012). English K-10 syllabus. file:///C:/Users/hwalker12/Downloads/english-k-10-syllabus-2012.pdf

Recourse Description and Access Toolkit (n.d.). Get started with the RDA Toolkit! http://access.rdatoolkit.org/

Scheffers, J. (2008). Guided inquiry: A learning journey. Scan, 27(4), 34-42.

Shi, R. (2020). What are the SCIS cataloguing standards? Schools Cataloguing Information Service. https://help.scisdata.com/hc/en-us/articles/115009544108-What-are-the-SCIS-cataloguing-standards-

Stone, A., Russell, R., & Patterson, K. (2004). Transformational versus servant leadership: a difference in leader focus. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25(3/4), 349-361.