ETL503 Assessment Item 2: Part B – Reflective Practice

Beginning with a broad snapshot in Module One, then gradually working through the principles underlying selection, acquisition and evaluation of resources, ‘ETL503: Resourcing the Curriculum’ has given me a firm grasp of each element of the collection development process in school libraries.

Firstly, selection. This element begins with analysis of the learners, educational philosophy, curriculum, and strengths and weaknesses of the current collection (Hughes-Hassell & Mancall, 2005, pp. 21 & 35-40). Next, using selection aids to identify appropriate resources (Johnson, 2018, p. 123). Then, applying selection criteria to the resources found and deciding whether the resources should be added to the collection (Johnson, 2018, p. 138).

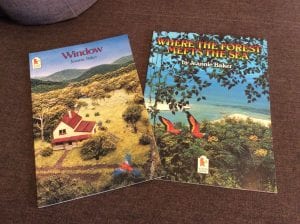

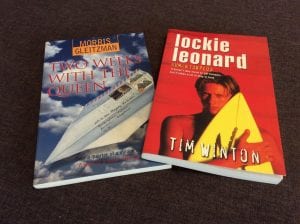

Even in the early stages of the course material it became clear – collection development must be based on the needs and requirements of the learning community (Hughes-Hassell & Mancall, 2005, p. 33; Johnson, 2018, p. 26). This principle was a constant thread from Module One to Module Seven. For example, in my Module Two blog post, A Fiction v Non-fiction Smackdown, I spoke about the tension between fiction and non-fiction texts used for reading assessments at a familiar school. My concluding statement proved that the library collection must have a balanced mixture of both to support the curriculum. Then, again, as part of the module on acquisition and access, the link between collection development and the needs of the community provided a basis for my post in Discussion Forum 3.2, from 9 April, about acquiring engaging levelled readers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students.

After considering legal and ethical issues around collection development, the course moved on to collection evaluation – analysing the collection to see how effective it is in fulfilling its purpose (Johnson, 2018, p. 281). I added a post to Discussion Forum 5.1 on 1 May about my favoured methods of collection analysis and wrote about the practicalities of collection evaluation at one particular school in my blog post, Evaluating the Collection. This post included a community needs-centred list of benefits highlighted by the National Library of New Zealand (n.d., “Why assess your library collection). Once again, the needs of the learning community were at the heart of another aspect of collection development.

There are many facets to collection development, as demonstrated. To ensure that the needs and requirements of the learning community are, indeed, met, school libraries should prepare a collection development policy (CDP). On one level, an effective CDP outlines selection, acquisition and evaluation principles (Johnson, 2018, p. 82), and guides library staff to make strong collection decisions. However, it also acts as a strategic document in a number of ways.

Most importantly, the document can be used to demonstrate the relevance of the school library and its collection in today’s educational climate, an important task for school librarians (Harvey, 2016, p. 131). With clear statements in writing, the CDP demonstrates to stakeholders that the library does have purpose, and does align with school and education department priorities (Johnson, 2018, pp. 82 & 86). Furthermore, the CDP demonstrates how the collection serves the learning community in a way that improves students’ achievement, and provides a platform for funding requests and budget allocations based on that information (Johnson, 2018, p. 86). The CDP guides staff in their responses to challenges to library resources, and prevents censorship and bias during selection and deselection processes (Johnson, 2018, p. 87).

Without all of this information documented in a clear, well-written policy, nobody knows what the library is doing now, or how the library is preparing for the what comes next (Johnson, 2018, p. 83).

It is our role to keep an ever-watchful eye on what’s on the horizon and where we might be heading in the future.”

Mitchell, 2011, p. 13

The school library exists as part of an information society, where information processes are at the heart of our cultural, technological, occupational, spatial and economic existence (Webster, 2014, p. 10). Through the collection, and the statements in the CDP, it is up to the school library to provide organised access to that information (IFLA, 2015, p. 17) as schools prepare students for life in an information-driven constantly-evolving 21st-Century world.

References

Harvey, C.A. II. (2016). The 21st-century elementary school library program: Managing for results (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, California: Libraries Unlimited.

Hughes-Hassell, S., & Mancall, J.C. (2005). Collection management for youth: Responding to the needs of learners. Chicago: American Library Association.

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). (2015). IFLA school library guidelines (2nd revised edition). Retrieved from https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/school-libraries-resource-centers/publications/ifla-school-library-guidelines.pdf

Johnson, P. (2018). Fundamentals of collection development and management (4th ed.). Chicago: ALA Editions.

Mitchell, P. (2011). Resourcing the 21st century online Australian Curriculum: The role of school libraries. The Journal for the School Information Professional, 15(2), 10-15. Retrieved from https://slav.org.au/FYI

National Library of New Zealand. (n.d.). Assessing your school library collection. Retrieved from https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/school-libraries/collections-and-resources/assessing-your-school-library-collection?search%5Bpath%5D=items&search%5Btext%5D=assessing+your+school+library+collection

Webster, F. (2014). Theories of the information society. 4th ed. London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.