Part A

Personal Philosophy

An effective teacher librarian is committed to supporting student engagement with, and access to, information and literature resources. They advocate for, and build effective library and information services and programs, to scaffold and implement the vision of a school community. Through collaborative and responsive practice, effective teacher librarians facilitate and enhance student learning and wellbeing. They empower their school communities to be information literate, and to embrace a culture of reading.

Part B

Children’s literature

Exploring children’s literature for ETL402 was a highlight of my studies, as this topic has been central in driving my goal of becoming a teacher librarian (TL) (Kimball, 2022). The subject consolidated my own views that children’s literature is a powerful thing; for a young person’s emotional, imaginative, social, and intellectual growth. For decades, research has informed educators that children’s literature supports all aspects of literacy development, including language development (Chomsky, 1972; Galda & Cullinan, 2003; Morrow, 1992), writing skills (Galda & Cullinan, 2003; Lancia, 1997), and reading comprehension skills (Galda & Cullinan, 2003; Haven, 2007; Morrow, 1992). Being a teacher, I was well aware of the academic benefits of reading, so I was particularly interested to learn more about the other benefits of reading, as well as how to embed literature across the curriculum, to support a more holistic view of student development.

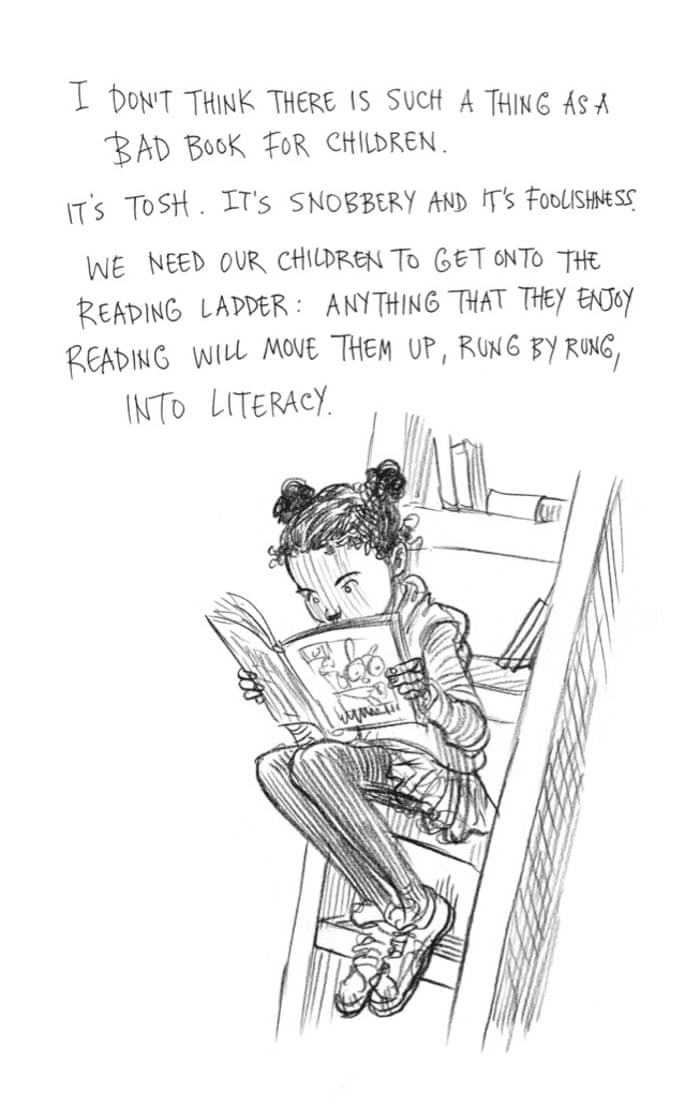

I have learned that a core component of the TL role is to promote a culture of reading, while empowering students to access literature of their choice, to support their development as independent readers. Research continues to demonstrate that children who are engaged with reading for pleasure are more likely to have success at school (OECD, 2011; Whitten et al., 2016). Creating these independent readers is a key challenge for TLs, teachers and parents, who may be concerned about the quality of student selections. It was reassuring to encounter professional opinions that strengthened my views, that educators and adults should not take an elitist position, where children are discouraged from reading what they enjoy (Gamble, 2019, p.7; Gaiman, 2013).

Figure 1

Neil Gaiman and Chris Riddell on why we need libraries – an essay in pictures.

Note From a series of text and images published in The Guardian (2018, September 18). In the public domain. From Art Matters, by N. Gaiman, illustrated by C. Riddell, 2018, Headline.

TLs should continue to provide these undemanding books, which may be predictable narratives in a series, graphic novels, or silly stories with comic illustrations, as they can be the texts that hook students into reading, as articulated in Figure 1. It is, however, also the role of the TL to promote other literary options, which convey significant themes or literary devices, to engage and stimulate young people’s intellects and imaginations.

At the start of ETL402, I viewed and read Gaiman’s inspirational lecture for the Reading Agency (2013), where he advocates for reading for pleasure, and specifically, for reading fiction. He argues that children’s fiction does two things; firstly, it is the hook to reading and literacy, and secondly, it has the power to build empathy (2013). As fiction promotes empathy-building and perspective taking, it has the potential to scaffold the development of children’s socio-emotional skills. Like Gaiman (2013), I believe that fiction can support young people to be more than self-focussed individuals; through literature, children do not just encounter new words, they also envision new worlds, and consider alternative ways of thinking and being.

I delved deeper into the connection between children’s literature and empathy, to explore how literature can embed additional outcomes to literacy development. In my first assessment for ETL402, I discussed how the Australian Curriculum’s (AC) General capabilities of personal and social capability, and intercultural understanding, can be supported through quality children’s literature. I referenced Kurcirkova’s conceptual paper, which investigated how children’s literature can be used to promote empathy (2019). Based on developmental psychology and literary theory, her research indicates that the ideal framework for effective empathy-building involves two features: children’s high immersion in the narrative, and a strong identification with characters who are different to themselves (Kucirkova, 2019, p.9). As a result, while students should select their own reading materials, TLs also have a responsibility to introduce children to a varied and engaging range of literary texts that explore diverse characters, settings, and events that are unlike their own lived experiences.

One of my professional goals for my placement at St Columba’s primary school library was to participate in library sessions across year levels, “which embed children’s literature and foster a positive reading culture within the school” (Kimball, 2023). At St Columba’s, I was fortunate to participate in literary experiences that introduced students to a range of quality literature, which was also highly engaging. This included author visits to inspire reading, writing, and literary discussion, literature circles to support the English curriculum, Cross-curriculum priorities and the General capabilities, and integrated literacy, arts and/or technology lessons, which explored the Children’s Book Council of Australia (CBCA) shortlisted picture books. During these library sessions, students developed a range of academic, personal, and social skills, while being immersed in children’s literature. The majority of students would not have selected the literature explored independently, highlighting the potential impact that TLs have on supporting students to become independent readers and successful learners.

The TLs at St Columba’s frequently encourage their school community to read widely, and to read for enjoyment. They had recently introduced new expectations for borrowing; students from Year 2 onwards were required to borrow at least one fiction, one nonfiction, one picture book (either junior fiction or older readers) and an extra book of their choice. These parameters promoted student choice, while also ensuring students were exploring the full library collection. The TLs also spend time at the start of library lessons to promote a variety of texts from different genres, authors and formats, and to discuss their location, having recently weeded and reorganised the collection.

Inspired by practising TLs who keep their collection fresh and inviting for students, while promoting quality literature alongside student favourites, I’m excited to continue my own professional journey and interests in children’s literature. It will be a pleasure to provide a service that elevates and promotes reading, and supports young people to connect with their interests, engage with ideas and perspectives, and imagine possibilities.

Information literacy

Information literacy (IL) has been another core theme in my journey towards teacher librarianship. With the introductory subject of ETL401, which grounded the whole course in the context of our rapidly shifting and developing 21st century information landscape, supporting students to be information literate was firmly positioned as central to the role of the TL. In the educational context, IL can be defined as a transformational process, whereby students develop from ignorance to knowledge, by accessing and using information (Fitzgerald, 2019).

As a teacher, I was aware of inquiry skills and inquiry learning, however, I hadn’t connected IL explicitly to the inquiry process. I was also unaware of the various inquiry or IL models and ways of interpreting IL, such as the Six Frames for IL (Kimball, 2019). I quickly learnt that TLs should be driving IL skills and processes, which are embedded within the AC’s General capabilities. As I was aware of the absence of explicit IL instruction in many primary school contexts, it was interesting, though not surprising, to learn through the work of Lupton (2014) and Bonanno (2015), that the AC lacks a clear scope and sequence of IL skills.

For Assessment item 3 of ETL401, I decided to further investigate the Guided Inquiry Design (GID) process, as an ideal model of IL, which would support the development of a process approach to IL, as argued by Fitzgerald (2019). The GID model is based on Guided Inquiry theory and practice developed my Kuhlthau, Maniotes, and Caspari (2015), which was developed from Kuhlthau’s (1989) Information Search Process. As discussed in my assessment, part of the appeal of the GID model is that it is evidence-based, and incorporates the perspective of the student researcher, with an emphasis on their predicted emotions (Fitzgerald 2019, p. 18-19). This explicit engagement with and acknowledgement of the emotions involved with inquiry and research tasks supports the development of student’s emotional resilience when learning; an area of focus which I’m building upon in my professional practice as a teacher.

While in theory my GID plan looked great on paper, in reality, I am yet to experience a primary school context where the TL is team-teaching a model of IL, with the luxury of an hour-long lesson. In planning for my professional placement, I hoped to observe IL in practice, with the inclusion of my professional goal, “to understand how information literacy skills and programs are implemented to enhance a variety of key learning areas” (Kimball, 2023). Unfortunately, when I was visiting St Columba’s Primary school library, Term 3 did not include the explicit embedding of IL programs, as all year levels were focussed on learning around literature and the CBCA shortlisted books. While aspects of IL occurred on a daily basis, such as developing student ability to locate resources using Oliver, the other school terms were mapped out for implementing IL. For example, in Term 2, the Year 2 students engage in a research task on an Australian animal, integrating English, Science and HASS, and incorporating the General capabilities of literacy, critical and creative thinking, and ICT capabilities. The TLs use Braxton’s (2015) Information Literacy Process (ILP) in 40-minute library lessons, with students publishing their research with Book Creator.

Key additions to the ILP are the steps ‘interpreting’ and ‘reflecting’, as defined by Braxton (2015), which the TLs at St Columba’s include in their planning documents. I recently created an infographic suitable for primary school contexts, Figure 2, to share with my colleagues, who are concerned that their students are not developing IL skills. The infographic includes the vital interpreting phase, and combines the assessing and reflecting phases.

Figure 2

The information literacy process

Note Infographic created with Canva 2023. Adapted from The Information Literacy Process, by B. Braxton, 2015, 500 Hats Blog. CC BY-NC-SA-3.0

While engaging with the recent study visits, I found the Lake Tuggeranong College (LTC) Library website and resources helpful and practical, with IL resources to add to my own repertoire of TL tools. An aspect of IL I have found particularly necessary and urgent, is skill development around evaluating websites and online information. LTC Library includes a ‘Keys to Success’ tab on their website, with a webinar link and PDF of slides for website evaluation. As I have used the ‘CRAAP test’ with my own students, I was interested to learn more about the S.I.F.T. method which the LTC library recommend.

Mike Caulfield (2018) has produced a series of videos, Online verification skills, as shared in Figure 3, which explain strategies to support website evaluation, linked to the S.I.F.T. method.

Figure 3

Online verification skills

As my current Year 6 students were examining news in the media for their English unit, I developed a S.I.F.T. infographic (Figure 4) and shared the Caulfield strategies, such as ‘hovering’ and ‘just add Wikipedia’. My students and colleagues responded positively to these IL processes and strategies, as practical resources that are applicable to various learning and personal contexts.

Figure 4

The S.I.F.T. Method

Note Infographic created with Canva 2023. Adapted from SIFT (The Four Moves), by M. Caulfield, 2019, Hapgood Blog. CC BY 4.0.

Supporting students to be information literate individuals is an enormous challenge, in our current climate of ubiquitous social media, data smog, and unregulated AI technologies. The rapid spread of the mis- or disinformation landscape has continued to rise and infiltrate daily life; whether young people are actively seeking, or, passively consuming information or infotainment, it is vital that educators and TLs support students to develop the IL skills to help them to make sense of this clutter, make informed choices, and to hopefully, move from ignorance to knowledge.

Resourcing the curriculum

Another critical aspect of the TL role is collaborating with teachers and the leadership team to resource the curriculum, ensuring a balanced school library collection. Throughout my teaching career, I’ve always enjoyed finding and sharing resources that strengthen and enliven learning areas for students. Consequently, through ETL503, I particularly enjoyed investigating selection criteria and developing an annotated bibliography, and was interested to learn more about how the TL engages in collection development and management, and what challenges are involved.

Initially, my first challenge was defining the terms, as I was confused about the difference between the concepts (Kimball, 2020). Corrall (2018, p.5) clearly differentiated between the two, with collection management the broader umbrella term which refers to a wide range of tasks regarding how to manage the library collection, whereas collection development refers specifically to the selection and de-selection of library resources. For Assessment item 1 of ETL503, I developed a diagram to represent the collection development process (Figure 5), adapted from Bishop (2013), Kimmel (2014) and the National Library of New Zealand (2012, cited in O’Connell, 2017).

Figure 5

Collection development process

This diagram helped me to understand the layers and key steps involved in collection development. While the collection development policy (CDP) is the first point of call in the process, I reasoned that there were at least four components informing the CPD. The following three steps then inform the TL, who can facilitate the selection of resources. Importantly, this process is an ongoing cycle, which I could have better represented with a more cyclical flow chart.

The CDP plays a foundational role in the selection process, which was a key take-away from ETL503, and an area to further investigate for my own professional development. I was surprised to learn that there wasn’t a CDP at my current school, given how important this policy document is for guiding the development and management of a school collection, and explaining why the collection exists (ALIA & VCTL, 2017, p.2; Johnson, 2018, p.86). In the ETL512 Virtual study visit discussion forum, I asked Tehani Croft about West Moreton Anglican College’s (WestMAC) CDP and needs assessments. Her team were currently undertaking a major rework of their CDP, and consequently she wasn’t confident in sharing their outdated document (personal communication, April 26, 2023). Unfortunately, the TLs at St Columba’s Primary school library also didn’t have a CDP. While I certainly understand the demands of workload and time constraints in school contexts, when I’m employed as a TL, one of my professional goals is to create a concise, informative, and readable CDP.

In reaching out to other TLs who work in state school contexts in my local area, I was able to make a valuable connection with an experienced and highly organised TL, who shared her CDP, which she includes in an annual report for her school principal. She emphasized the importance of this practical document, which is reviewed annually, as it supports and justifies the school library budget, resources for selection, as well as her professional role. The TLs at St Columba’s and WestMAC both articulated their fortunate position that securing a decent budget allocation wasn’t a problem for their well-resourced libraries. The situation is very different at the coal-face of many state school libraries; perhaps because Australian public schools are still shockingly underfunded by state and federal governments, despite the Gonski recommendations from 2012 (Crotty, 2023, p.9). By visiting a range of school libraries, I’ve certainly witnessed a cultural and economic divide in our education systems, and consequently, in school libraries. Clearly, if we’re serious about improving literacy rates, we need full funding for state schools now (Figure 6).

Figure 6

For Every Child fair funding campaign

Note “For Every Child” is a campaign of the Australian Education Union. In the public domain.

As I discussed in my blog post, May 11 (Kimball, 2020), Johnson emphasizes the purpose of CDPs as being twofold; to inform and to protect (2018, p.86). CDPs can be powerful tools for assisting with budgeting, as they should provide information for proposed budget allocation and for funding requests (Braxton, 2015; Johnson, 2018). They are also a vital document to protect intellectual freedom and prevent censorship, and to empower TLs to be prepared should resources from the collection be challenged (Braxton, 2015; Johnson, 2018). While on my professional placement, the TLs discussed texts which had been challenged, and how the needed to refer to their school policy of embracing diversity and inclusion, as they don’t have a CDP. So far, this arrangement has been adequate for them, however, they also acknowledged they would like to develop one, to further strengthen and protect their diverse collection.

In recent professional literature and practice, there has been the timely discussion and action of ‘decolonising’ the school library (Klimm & Robertson, 2021). This is the process of weeding and deselecting material from the collection which includes misinformation about Australia’s Indigenous history and people, or perpetuates racist stereotypes. For Assessment item 1, I developed an annotated bibliography to address the AC’s Cross-curriculum priority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures (ATSIHC). I’ve since been able to share this document with my colleagues, and am pleased the general selection criteria I applied, particularly in relation to accuracy, treatment, and authority, included specific points to consider in relation to ATSIHC. I’ve recently located a number of nonfiction books in my school library which should be removed from the collection, and aim to work with our TL to evaluate and deselect them. In support of change, Indigenous recognition, and a commitment to accurate information, the collection development and management process continues.

PART C

The Master of Education (Teacher Librarianship) course has given me a wealth of new skills and understandings for application to the role of TL. Yet, as I now complete my formal studies to achieve the TL qualification, I’m somewhat anxious at the prospect of working in the role, given the cyclical paradox of higher education, where the more you know, the more you know you don’t know. Fortunately, my confidence was boosted when I participated in my professional placement, where I felt comfortable and competent in my abilities, and was valued as part of a library and teaching team. This final, practical component of the course has been essential for consolidating and applying my new knowledge, and for supporting my professional development as a graduate TL.

In reflecting on what I’ve learnt in this course, and how this will assist me in developing my skills and attitudes as a professional TL, the Standards of professional excellence for teacher librarians (ASLA/ALIA, 2004) provides a framework for considering ongoing professional development. Divided into twelve standards across the three domains of Professional knowledge, Professional practice, and Professional commitment, I’ve found this framework useful when also supported by the AITSL (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership) Standards and teacher librarian practice document (ALIA Schools, 2014). As all teachers in Australian schools are required to refer to AITSL’s Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (2017) when completing their Annual Performance Development Plan (APDP), ALIA’s document is a useful bridge between the two sets of standards.

Central to the TL course has been an emphasis on the rapid development and changes within the information and education landscapes, as well as the importance of future-proofing our school libraries. Consequently, in order to achieve the status of an excellent TL, I will need to continually update my specialist knowledge and skills, as articulated in standard 3.1, Lifelong learning (Professional commitment). In support of this goal, the continued development of my digital literacy skills will be a priority, as it has been throughout my teaching career, in order to support a community of library users to access and use relevant information resources.

My continued development of digital literacy skills will also enable me to effectively demonstrate standard 2.3, Library and information services management (Professional practice). This standard requires specialist knowledge of information services, resources, technology and library management, which will require site-specific upskilling and application. Historically, I’ve found accessing the skills and knowledge of colleagues particularly helpful when seeking practical professional development. In support of standards 3.1 and 2.3, will also be my skill development in creating and maintaining a CDP, as discussed in this portfolio. As I work towards this goal, I’ll continue to strengthen standard 3.4 Community responsibilities (Professional commitment), as I aim to actively engage with professional school library communities that I’ve begun to connect with, as a result of my TL studies.

The last four and a half years have been an incredible learning experience, a feat of endurance at times, and I’ve acquired a fantastic repertoire of library, education, communication, information and digital literacy skills and tools. While I’m not an “excellent teacher librarian” yet, I believe I have the capacity! I have been fortunate to experience supportive collegiality within the TL community, and I look forward to finally joining the ranks, to reciprocate and contribute to this essential service of our society.

References

Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA). (2004). Standards of professional excellence for teacher librarians. https://read.alia.org.au/alia-asla-standards-professional-excellence-teacher-librarians

Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA). (2014). AITSL (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership) Standards and teacher librarian practice. https://www.alia.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/ALIA-Docs/Communities/ALIA%20Schools/AITSL-Standards-for-teacher-librarian-practice-2014.pdf

Australian Library and Information Association Schools and Victorian Catholic Teacher Librarians. (2017). A manual for developing policies and procedures in Australian school library resource centres (Revised edition). file:///E:/CSU/ETL503%20Resourcing%20the%20Curriculum/ALIA%20Schools%20policies%20and%20procedures%20manual_FINAL.pdf

Bishop, K. (2013). The collection program in schools: Concepts and practices (5th ed.). Libraries Unlimited.

Bonanno, K., (2015). F-10 Inquiry skills scope and sequence and F-10 core skills and tools. Eduwebinar Pty Ltd. https://eduwebinar.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/curriculum_mapping_scope_sequence_skills_tools.pdf

Braxton, B. (2015). The information literacy process. 500 Hats: The teacher librarian in the 21st century. https://500hats.edublogs.org/files/2015/09/il_process_summary_2015-1dmyz8p.pdf

Braxton, B. (2015). Sample collection policy. 500 Hats: The teacher librarian in the 21st century. https://500hats.edublogs.org/policies/sample-collection-policy/

Bruce, C., Edwards, C., & Lupton, M. (2007). Six frames for information literacy education. In S. Andretta (Ed.). Change and challenge: Information literacy for the 21st century. Auslib Press.

Caulfield, M. (2019, June 19). SIFT (The Four Moves). Hapgood. https://hapgood.us/2019/06/19/sift-the-four-moves/

Chomsky, C. (1972). Stages in language development and reading exposure. Harvard Educational Review, 42, 1-33.

Corrall, S. (2018). The concept of collection development in the digital world. In M. Fieldhouse & A. Marshall (Eds.), Collection development in the digital age (pp. 3-43). Cambridge University Press.

Crotty, B. (2023). For every child – fully fund state schools. In Queensland Teachers’ Journal, 128(6), 9. https://www.qtu.asn.au/3d/Vol128No6/index.html

Fitzgerald, L. (2019). Guided Inquiry goes global: Evidence-based practice in action. Libraries Unlimited.

Gaiman, N. (2013, October 16). Why our futures depend on libraries, reading, and imagination. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming

Gaiman, N. (2018, September 7). Neil Gaiman and Chris Riddell on why we need libraries – an essay in pictures. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2018/sep/06/neil-gaiman-and-chris-riddell-on-why-we-need-libraries-an-essay-in-pictures#img-5

Galda, L., & Cullinan, B. E. (2003). Literature for literacy: What research says about the benefits of using trade books in the classroom. In J. F. Hood, D. Lapp, J. R. Squire, & J. M. Jensen (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching the English language arts (pp. 640-648).

Gamble, N. (2019). Exploring children’s literature: Reading for knowledge, understanding and pleasure (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Haven, K. (2007). Story proof: The science behind the startling power of story. Libraries Unlimited.

Johnson, P. (2018). Fundamentals of collection development and management (4th ed.). American Library Association Edition.

Kimball, A. (2022, May 22). Children’s literature. Reflective Blog. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/alyssa/2022/05/22/childrens-literature/

Kimball, A. (2019, September 29). ETL401 Module 5.2 Information Literacy in education. Reflective Blog. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/alyssa/2019/09/29/etl401-module-5-2-information-literacy-in-education/

Kimball, A. (2020, May 25). ETL503 Reflective practice (Assessment 2: Part B). Reflective Blog. https://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/alyssa/2020/05/

Kimball, A (2023). Assessment item 4 – Placement proposal and CV. [Unpublished assignment submitted for ETL402]. Charles Sturt University.

Kimmel, S.C. (2014). Developing collections to empower learners. American Library Association.

Klimm, K., & Robertson, D. (2021). How an old book created a commitment to better represent first nations Australians. Connections, 117, 4-5.

Kucirkova, N. (2019). How could children’s storybooks promote empathy? A conceptual framework based on developmental psychology and literary theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(121), 1-15.

Kuhlthau, C.C. (1989). Information search process: A summary of research and implications for school library media programs. School Library Media Quarterly, 18(1), 1-12.

Kuhlthau, C.C., Maniotes, L.K., & Caspari, A.K. (2015). GI: Learning in the 21st century (2nd ed.) Libraries Unlimited.

Lancia, P.J. (1997). Literary borrowing: The effects of literature on children’s writing. The Reading Teacher, 50, 470-475.

Lupton, M. (2014). Inquiry skills in the Australian Curriculum v6: A bird’s-eye view, ACCESS, 28(4), 8-29. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/78451/1/Lupton_ACCESS_Nov_2014_2pg.pdf

Morrow, L.M. (1992). The impact of a literature-based program on literacy achievement, use of literature, and attitudes of children from minority backgrounds. Reading Research Quarterly, 27, 250-275.

O’Connell, J. (2017). School Libraries. In I. Abdullahi (Ed.), Global Library and Information Science (2nd ed., pp. 375-393). Walter de Gruyter.

Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development. (2011). Do students today read for pleasure? PISA in Focus, 8, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/pisainfocus/48624701.pdf

Whitten, C., Labby, S., & Sullivan, S. (2016). The impact of pleasure reading on academic success. The Journal of Multidisciplinary Graduate Research, 2(4), 48-64.